Sophie Bissonnette, Léa Roback, Madeleine Parent.

Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent are two key figures in the history of Quebec. Filmmaker Sophie Bissonnette produced two important documentaries about them: A Vision in the Darkness and Madeleine Parent, tisserande de solidarités. Once the two films were edited, much of the interview material with the two pioneers of feminism and trade unionism remained unreleased.

Those archived documents are now available through this special project, which features a dozen hours of video clips organized by theme and accompanied by explanatory texts by two eminent historians. The interviews reveal the little-known history of women’s movements from the 1930s to the 2000s, including those of garment and textile workers, Indigenous and immigrant women, and all those who fought for fair pay and the right to abortion. Through this special project, we aim to provide insight into the lives and achievements of two exceptional women, who have inspired generations to strive for a fairer, more equitable world.

Élisabeth Meunier, Director of Conservation and Collection Development

For the past few years, the Cinémathèque québécoise has endeavoured to highlight the contributions of independent feminist cinema in Quebec by restoring and showcasing the works of female directors. Our first special project about Sophie Bissonnette, entitled Au cœur de la mouvance féministe, les films de Sophie Bissonnette [Inside the Feminist Movement: The Films of Sophie Bissonnette], reflected this spirit by providing access to all the films made by this pioneer of independent documentary cinema. This latest project, entitled Pioneers of Feminism and Unionism: Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent, focuses on two illustrious women who were the subjects of two films by Bissonnette. Drawing on outtakes from our collections, this project not only highlights the importance of these two women in the history of Quebec, but also reaffirms the major role played by Sophie Bissonnette’s work in safeguarding and sharing the history of feminist struggles.

This “re-creation” project, featuring archived material, aligns with Sophie Bissonnette’s artistic approach and reflects her desire to reconsider the dominant narratives and raise the profiles of women, particularly those who have been marginalized. Her approach has been apparent since the very beginning of her career in the late 1970s, when she first became aware of the “missing images” of our history: non-existent archived images of women; concealed or biased—and even misleading—accounts of their contributions; narratives in which they were relegated to the role of victim . . . For the past forty years, Bissonnette has focused mainly on documentary filmmaking, with the aim of highlighting the contributions of women to Quebec’s history and to society as a whole.

For the Pioneers of Feminism and Unionism: Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent project, the filmmaker selected original footage, including excerpts from interviews she had conducted for the documentary films A Vision in the Darkness (1991) and Madeleine Parent, tisserande de solidarités (2002), which did not appear in the films’ final cuts. In view of the historical content and the invaluable personal accounts recorded in this material, the footage was digitized, edited, and put into context by historians, in order to bring to light important but little-known chapters in Quebec’s history. For although Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent are rather widely known, their central roles as feminists and union activists have remained largely undiscovered. To rectify the situation, nearly twelve hours of footage from previously unseen interviews, presented in segments lasting from three to thirty-one minutes each, have been made available for viewing. They have been arranged chronologically and by theme and supplemented by written texts by historians Denyse Baillargeon and Andrée Lévesque. These unedited excerpts, presented as raw material, reveal the mindsets and personalities of the two activists, as well as the process of making the documentary films. The project also includes bibliographical references. For an overview of the lives of the two activists, we recommend watching A Vision in the Darkness and Madeleine Parent, tisserande de solidarités.

We hope you find these videos and texts inspiring and thought-provoking, and that you enjoy this informative project!

I have had the great privilege of meeting and getting to know both Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent, two remarkable, “dangerous” women, who displayed courage and boldness by standing up for those who were most exploited by society and speaking out for women at a time when they were scorned and written out of history. Although I am very pleased that my films have helped shed light on the stories of these women, whose actions left their mark on the history of Quebec, I have always found it unfortunate that so much information, and so many interesting anecdotes, had to be omitted. In fact, I shot dozens of hours of interview footage with Léa and Madeleine, only a portion of which ended up in the films. I found this particularly regrettable, given that I have often been confronted with a frustrating lack of records, images, and quotes of women with which to tell their stories. Documentary filmmakers often find themselves the custodians of untold, invaluable pieces of history, and it was unacceptable to me that these archives should fade into oblivion.

So I was delighted to bring this project to life in collaboration with the Cinémathèque québécoise, the Réseau Québécois en Études Féministes, and historians Denyse Baillargeon and Andrée Lévesque. Several boxes of 16mm reels and Betacam cassettes, which had been in storage for decades, were removed from the vaults of the Cinémathèque and digitized. I then edited significant excerpts of my interviews with Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent.

The origins of the two films are very different. A Vision in the Darkness was a personal project in which I wanted to retell the history of women in early twentieth-century Quebec, from a modernist, feminist perspective. When I met Léa Roback for the first time, she was 85 years old. I immediately became enamoured of this spirited, witty woman who never let anything faze her. Léa told her stories in a very spontaneous, rapid-fire manner. Each one was more enlightening and hilarious than the last. Her storytelling style was distinctive and unique.

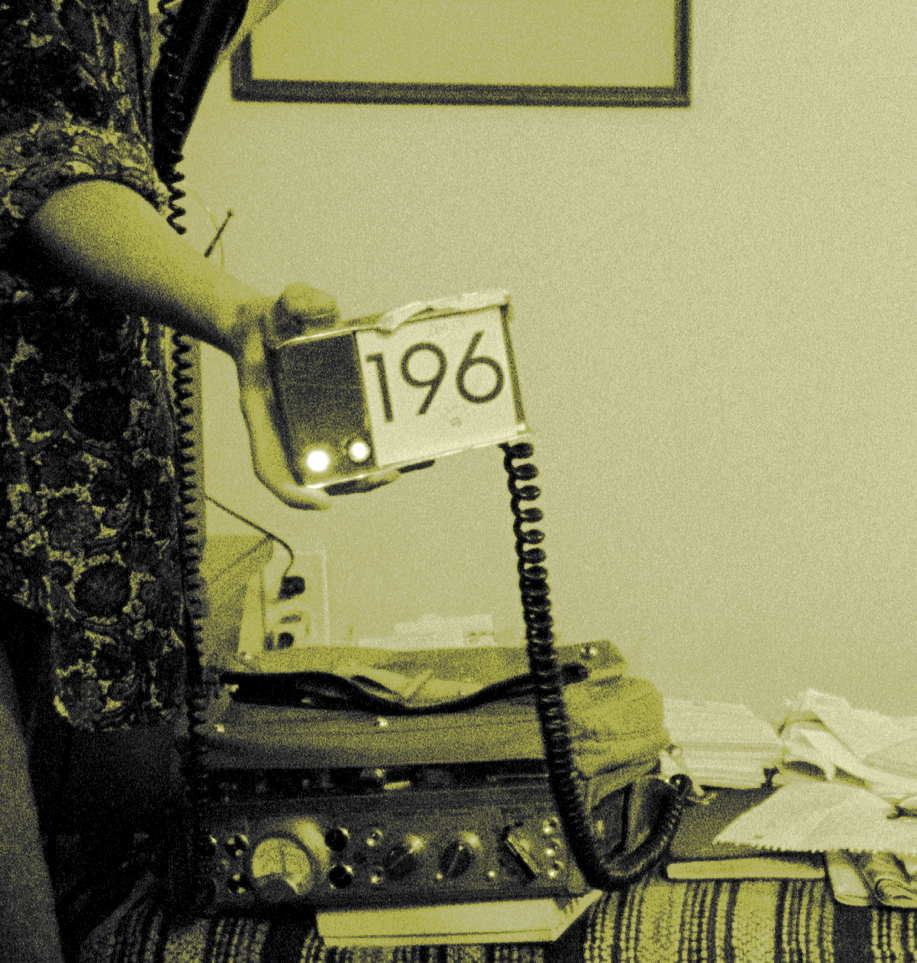

With Martin Leclerc and Serge Giguère on 16mm camera and Marie-France Delagrave on sound, I shot approximately six hours of interviews with Léa between September and December 1989. After a year of editing the footage with Dominique Sicotte, weaving together Léa’s story and that of the female workers of the first half of the century, I returned small reels of film and videocassettes to the boxes, as they did not appear in the final version of the film. The reasons for this varied. Some of the topics had not been sufficiently developed, others were too broad or they slowed down the narrative structure, still others were difficult to incorporate into the film’s major themes. For documentary filmmakers, the editing process is basically a series of mourning sessions as the film takes shape.

Madeleine Parent, tisserande de solidarités came into being in a very different way. Ten years after I released the film about Léa, I was asked by a colleague, Judith Murray, to conduct interviews with Madeleine Parent, who was then 81 years old, with a view to compiling an archive. Judith had been in contact with Madeleine, who wished to tell her story. With Judith and me, as well as with Martin Duckworth on camera, she felt at ease. She had selected the events she wished to commit to posterity and had carefully prepared for the interviews, making notes about events, dates, and the names of those involved. Judith’s questions, as well as my own, were formulated to ensure we covered all the subject matter that had been selected. However, our own curiosity caused us to stray from our scripts from time to time.

Upon meeting Madeleine for the first time, I felt rather intimidated by this woman who had stood up to multinational companies, to premiers (including “Le Chef” [The Boss] in Quebec!), and to the Quebec and Ontario provincial police; a woman who was willing to risk going to prison to defend the workers she represented; and a visionary who founded a labour confederation, led successful union battles, and contributed to the advancement of women. Phew! Madeleine welcomed me with a big smile and a gentle manner, and she generously told me all about herself. Over four afternoons of filming at her home, my apprehensions melted away and my shyness turned into admiration as I became an intimate witness to her life story.

In August and September 1999, we shot twelve hours of interview footage with Madeleine, on twenty-two Betacam videocassettes. A year later, Monique Simard, who was then a producer at Productions Virage, as well as a friend and neighbour of Madeleine’s, obtained funding to make a 45-minute film using the material we had shot. Given those time constraints, we agreed with Madeleine that we would focus on her work in Quebec from 1937 to 1952 as a union organizer in the textile industry, including the epic strikes at Dominion Textile and her trial for seditious conspiracy. Much to our chagrin, we therefore had to leave out some of her most significant endeavours, such as her role as co-founder of the Confederation of Canadian Unions, the major battles she waged alongside immigrant and racialized women in Ontario, her influence in the creation of an independent feminist organization in Canada, her work in advancing demands specific to women in the workplace, and her role in supporting the struggles of Indigenous women from the early 1970s onward.

Before digitizing the interview material, I selected some of the reels, particularly those shot with Léa in double-system 16mm (image and sound on separate media), given the high cost of that type of digitization. With the collaboration of historian Denyse Baillargeon, and using the transcriptions that had been made at the time of shooting, I selected the excerpts we felt had the greatest historical value and which had not been given much coverage in other interviews with Léa. I had also interviewed Madeleine for the film about Léa, so I kept excerpts from that shoot to supplement the interviews with Madeleine later on. The interviews with Madeleine had been shot in SD video on Betacam SP cassettes, so all of them were digitized. During the editing process, I had historian Andrée Lévesque approve my selections. I also included footage of a meeting between Françoise David and Madeleine Parent in October 2000, a shoot that had been planned specifically for the film about Madeleine.

The selected reels and videocassettes were then digitized in high definition at various laboratories (the National Film Board of Canada, MELS in Montréal, and VTape in Toronto). Several of the shots that had been recorded on film had to be painstakingly re-synchronized by hand.

During the editing process, I grouped the excerpts together by theme and chronology. I opted for a transparent approach that showed the raw material and the shooting process. For example, when editing, I retained the clapperboard, the director’s questions, the crew’s comments, the ends of the cassettes or the reels, the stand-alone audio when the 16mm camera wasn’t running, and the missing 16mm images that had been used for the original film. So, as you watch these clips, prepare to experience a documentary shoot! You’ll watch the daylight fade during an interview with Madeleine Parent, and you’ll see the dancing shadows of a tree’s leaves on the wall behind her. You’ll hear the wind howl through a window at Léa Roback’s house during one of her interviews. Their interviews will be interrupted by the running out of a reel (about 10 minutes in 16 mm) or a cassette (30 minutes in Betacam), by someone ringing the doorbell, and by the sound operator’s annoyed voice announcing that his recorder’s battery is dying. You’ll also hear a certain director (who had never imagined that her questions would one day be broadcast) stumble over her questions and stammer . . .

The post-production work was carried out in the same spirit. During the colourization and sound mixing stages, we did not attempt to hide the technical difficulties that are inherent to a shoot, compensate for the natural lighting that evolved throughout the interviews due to the changing positions of the sun and the clouds, or mask the external elements (traffic, airplanes, wind) that affected the sound. However, we did make some slight modifications to ensure a clear, coherent viewing experience. During mixing, we adjusted the volumes and equalized the voices to make the content more understandable and pleasant to listen to, and we minimized disruptive sounds such as coughing, chairs being moved, etc. During the colourization process, to reflect the original colour tones and the intention of the shoots, we made the images look more natural, as the digitization (from analog to digital for the 16mm and from SD to HD for the videocassettes) and compression processes had inevitably resulted in certain changes.

This project has allowed me to rediscover the qualities that initially drew me to Léa and Madeleine. I hope you will find them as informative and inspiring as I do.

Denyse Baillargeon, specialist in women’s history and Professor Emeritus, Department of History, Université de Montréal *Andrée Lévesque, Professor Emeritus, Department of History, McGill *University

History cannot be written in the absence of documents to inform it and provide the content from which to construct a narrative and develop an interpretation of events. There was a time, however, when the documentation found in archival collections or considered worthy of interest centered mainly around activities that took place in the public sphere, such as business deals and political debates, and from which women had been all but excluded. As a result, written history has focused almost entirely on men’s achievements, as if they had singlehandedly built and shaped the world. Yet, as evidenced by this project, which aims to safeguard the legacies of two important female figures, women have played a fundamental role in history, both in Quebec and elsewhere.

But how can we shed light on women’s contributions to society? Where are the sources, the documents? In the late 1960s, these questions became increasingly compelling to historians as they began to explore the vast field of women’s history. The then-resurgent feminist movement, which sought to understand the origins of the patriarchy and the oppression of women, sparked great interest in the roles women had played in earlier societies. However, the first feminist historians to look into those issues quickly realized that traditional archival collections—those kept in “official” institutions—tended to reflect men’s achievements, and therefore did not provide much data that could help them. Even worse, they discovered that society’s lack of regard for women and for their actions had sometimes led to the outright destruction of documents they, or their organizations, had produced.

This lack of documentation quickly became one of the main challenges facing historians of women’s history. In addition to seeking answers to the new questions they were asking in the existing “official” documents, they also set out in search of hitherto ignored women’s and feminist writings (correspondence, diaries, autobiographies, petitions, association archives, etc.). They also elevated items that could bear witness to the lives of women in the past, such as department store catalogues and other relics of everyday life, to the status of historical source.

Of all the various strategies that have been used to document certain aspects of women’s historical experience, oral history—or, more precisely, the use of interviews—appears to have been one of the most effective. Despite the limitations of people’s memories, which can sometimes confuse dates or conflate events, oral sources are particularly valuable in that they are often the only sources of certain information. As such, any interview that sheds light on women’s aspirations, actions, or struggles contributes to the body of knowledge we have about them, and therefore contributes important information to their written history. Sophie Bissonnette’s documentary films about Léa Roback and Madeleine Parent, in which the two activists talk about their lives, as well as the previously unpublished excerpts from the interviews that are featured in this project, are prime examples of the types of documents sought within the movement to create women’s archives and better preserve their histories.

Léa Roback (1903-2000) and Madeleine Parent (1918-2012) were two exceptional women whose lives intersected, and who left their marks on Quebec’s major social movements of the twentieth century: trade unionism, feminism, and pacifism. In the interviews, which were conducted in 1990 and 2000, each woman tells her own story of the era in which she lived, as well as the struggles that shaped it.

Léa served as a mentor to Madeleine. The young student first met Léa, who was fifteen years her senior, at a Civil Liberties Union meeting at McGill University in 1939. Madeleine was inspired by the union activist’s efforts on behalf of the workers in the women’s clothing industry, and decided to follow in her footsteps. The rest is history. Like Léa, Madeleine became a union organizer at a time when the union movement was dominated by men. Both activists fought to improve working conditions for women; Léa did so in Montréal, and Madeleine did so in Montréal, Valleyfield, and Lachute, as well as in Ontario several years later. They fought the wartime exploitation of female workers, experienced North American McCarthyism and the anti-communism sentiment that was directed at all left-wing groups, and were subjected to raids under the Anti-Communist Propaganda Act, known as the “Padlock Act,” and the 1970 War Measures Act. They also endured the harassment and frustrations faced by women in largely male-dominated union environments, and paved the way in defending and upholding the rights of working women. Léa, who was sensitive to issues of racism, took part in the anti-racist movements of her time, condemning racism against Black people and apartheid in South Africa, and supporting the demands of immigrant women. In the strikes she led in Ontario, Madeleine focused on organizing immigrant women workers. She also defended the rights of Indigenous women, particularly those married to non-Indigenous men, when she served on the board of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women in Ottawa.

As pioneers of the feminist movement, who were keenly aware of the problems faced by working women, Léa and Madeleine took part in every battle: for access to abortion, for pay equity, against harassment and violence against women, and against women’s poverty. As the Cold War revived the pacifist movement, both became founding members of Voix des Femmes [the Montréal section of Voice of Women], which demonstrated against war, militarism, and imperialism.

Léa and Madeleine made no secret of the setbacks they faced, nor of the betrayals and disappointments they experienced, but they persisted in learning from their failures and refused to ever give up. As women of action, they helped bring about real change, improving the status of female workers, as well as their wages and work environments. Each in her own way was a trailblazer for the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. They both pushed for legislative changes that decriminalized abortion, promoted pay equity, and combatted discrimination based on race or ethnicity. These nearly twelve hours of never-before-seen interview footage provide access to their invaluable personal stories as they describe, in their own words, the battles they waged as activists for half a century.