In March 2022, the Spira distribution company donated its extensive Vidéo Femmes collection, comprising 350 titles produced between 1973 and 2014 and preserved on nearly one thousand cassettes and magnetic tapes, to the Cinémathèque québécoise. Although some of the items had been placed in the Cinémathèque’s reserves in the early 1990s, the collection had never received the visibility and recognition it rightly deserves. One of the objectives of this special project—the result of a collaboration between researcher Julia Minne, the directors of Vidéo Femmes, and the Cinémathèque—is to remedy this situation and shed new light on the importance of this feminist collective.

In order to tell the untold tale, Julia Minne opted for the interview format, which is perfectly suited to the approach and character of Vidéo Femmes. By letting those who worked with the organization over its forty-year existence recount their own experiences, this special project echoes one of the central tenets of the women’s films: giving women a voice and bearing witness to their personal experiences. In this spirit, the films of Vidéo Femmes did not reject the television model with which video was commonly associated at the time (distinguishing themselves in that respect from certain pioneering works of feminist video, such as those by Les Insoumuses or Valie Export, for example), but rather, embraced its social reach and community-wide accessibility. Not surprisingly, many of the filmmakers had their roots in community radio and television, from which they retained a penchant for reporting and vox populi, in their early films, at least. But in contrast to the cold detachment of televised news, these films generated genuine intimacy and created a rapport that led to sometimes deeply moving personal stories, such as those found in Chaperons rouges, C’est pas le pays des merveilles, and Juste pour me calmer, for example.

This proximity also testifies to the filmmakers’ on-the-ground work with women who faced problems and injustices that are all too often ignored, including depression, domestic violence, bullying, alcoholism, and so on. One of the findings of the video entitled Bilan du stage franco-québécois “Féminisme et communications” is that the actions of Vidéo Femmes did not stem from theoretical reflection, as was the case with their French compatriots, but rather from a concrete need, a grassroots reality (in women’s shelters, sexual assault centres, and family environments, for example). Bringing women’s voices to the fore and exposing the situations they faced were in themselves militant gestures in a media landscape that all too often concealed those realities. Indeed, upon reading the notes in this special file, we can have no doubt that these were women of action! Not only did they make films, but they also organized festivals, set up a distribution network, offered training courses to female videographers, and organized regional road shows. The longevity of Vidéo Femmes and the scope of its productions attest to the commitment and resilience of all those involved, despite the social, financial, and bureaucratic constraints that beset them along the way.

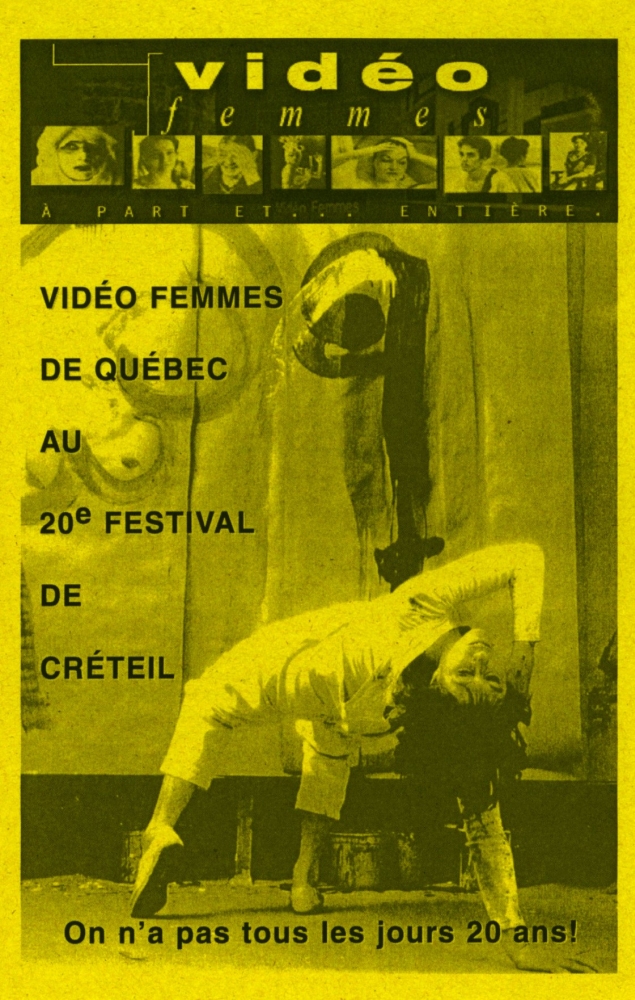

It would be wrong, however, to reduce Vidéo Femmes’ work to a purely social-interventionist style, devoid of any aesthetic appeal. From the outset, art was an integral aspect of the very essence of their films. Whether through theatre, performance art, music, dance, or poetry, art continually permeated the social discourse conveyed by the films, demonstrating how artistic expression is able to question the female condition and the socio-political structures in which it is ensconced. The young filmmakers also soon began experimenting with video equipment, which was still largely repudiated by the “legitimate” film industry of the time. Some of the works became progressively more daring, both in terms of form and subject matter, exploring docufiction (Poing final), collage film (Histoire infâme, Les Mots/Maux du silence), and even experimental film (Tatouages de la mémoire, Comme une tempête). Although certain effects such as saturation, chroma keying, and superimposition are now inextricably linked with a certain “retro” aesthetic typical of 1980s video, they nonetheless denote great creative freedom and a playful, inventive way of using the video medium. For example, the “lettrist” interlude in Demain la cinquantaine, which conveys the restlessness and anxieties of a woman in the throes of menopause, is still astonishing in its originality and intensity.

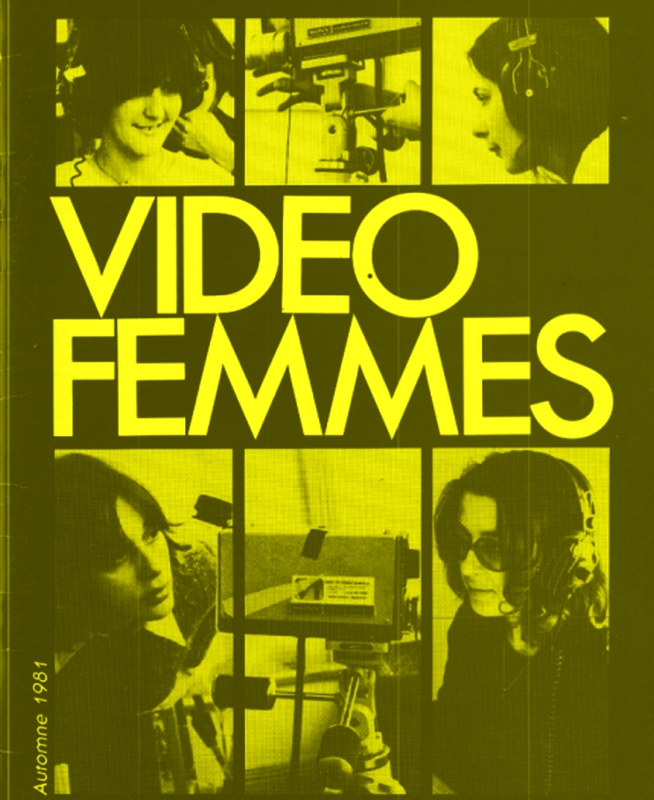

Ultimately, this special project provides us with the opportunity to reflect on the status of video and feminist works in our own collections and, more broadly, in heritage institutions in general. The “Vidéo Femmes: Archiving and Remediation” round table and the work of artist kimura byol invite us to question the Cinémathèque’s acquisition and distribution policies and its relationship to a form of production long considered inferior and extraneous to the artistic aspirations of “real” cinema. In 1975, when Helen Doyle and Nicole Giguère shot their first video at the Women’s Show, the video format was still intimately linked to television and the world of communications, not to that of cinema. It was seen as a necessary evil for the dissemination of cinema on the small screen, but film remained the only medium worthy of cinematographic work. At that time, the Cinémathèque was barely 10 years old and had just inaugurated its conservation centre in Boucherville. Its legitimacy was largely based on the acquisition of Quebec films and masterpieces of world cinema, as well as the projection of those works onto the big screen. Although video projection has existed in various forms since the 1930s, it did not become commonplace until the late 1980s, its widespread use having previously been hampered by low resolution and high costs. Video production thus found itself in the “blind spot” of traditional filmmaking, and instead developed in parallel networks, such as artist-run centres and social organizations.

But the position of the Cinémathèque gradually changed in the 2000s—admittedly not without some resistance, as is evidenced by some of the texts quoted in this project—as the explosion of media arts prompted us to revisit the history of video, particularly in Quebec. The 2011 appointment of Jean Gagnon as director of collections (himself a product of the video art milieu), the regular programming of video works in the Fernand-Seguin room, and the acquisition of the important collection of the Daniel-Langlois Foundation are all evidence of a change in attitude toward the historical impact of video and its legitimacy within the Cinémathèque’s collections. It is also worth mentioning the many warnings issued by the archive community about the deterioration of magnetic tapes, which are increasingly prone to sticky-shed syndrome, and the obsolescence of the playback equipment. The rapid deterioration of video supports prompted archival institutions, including the Cinémathèque québécoise, to take action and invest in this neglected audiovisual heritage, to ensure its survival and its continued enhancement.

This change in attitude must now be reflected in concrete action, which poses a number of challenges for an institution whose expertise has been built around film. In this respect, Julia Minne’s work at the Cinémathèque has laid the foundations for reflection on the conditions under which heritage media can be made visible, and it is now our duty to identify and revisit certain video collections that are capable of shedding light on certain communities and marginalized productions. This special project, like our project on the PRIM Centre in 2021, demonstrates the Cinémathèque’s nascent desire to promote its video holdings and flesh out the history of audiovisual production in Quebec. Thanks to the support of Heritage Canada’s Museums Assistance Program, this initiative has led to the digitization of dozens of items from the Fonds Vidéo Femmes, as well as of hundreds of archival documents that help contextualize this remarkable body of work and grasp its boldness and relevance. I therefore invite you to discover this rich heritage in the company of those who forged the history of feminist video in Quebec and generously contributed to the creation of this special project: Lise Bonenfant, Helen Doyle, Johanne Fournier, Nicole Giguère, Lucie Godbout, Ginette Gosselin, Hélène Roy, Lynda Roy, Nathalie Roy, and Sylvie Tremblay.