Unquestionably the decade of deployment, with the growing team: the production of major documentaries which will be the signature of Vidéo Femmes, the establishment of a vast film and video distribution network, the expansion of the "Festival des filles des vues". Interview conducted with Helen Doyle, Nicole Giguère, Johanne Fournier, Lynda Roy, Nathalie Roy, Lucie Godbout, Lise Bonenfant and Sylvie Tremblay.

A New Start: Experimenting with Hybrid Genres

Julia Minne: We are now in the 1980s. You’ve just changed your name to Vidéo Femmes and have moved to 10 McMahon Street in Old Quebec City. How was the collective structured from that point onward?

Johanne Fournier: Our offices were located on the third floor of a heritage building that belonged to Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, in the heart of the Latin Quarter, with all the restaurants, theatres, bars, and everything else that was around there at that time. We had half of the third floor. When we went out to shoot, the car would be parked on the street . . . a very small one-way street, very narrow, so . . .

Nicole Giguère: We had to move fast!

JF: There were always cars behind us, honking at us!

NG: Our slogan was “d’abord déménageuses” [movers first], in reference to the film D’abord ménagères [Housewives First] by Luce Guilbeault. We often had to bring our equipment with us.

Lynda Roy: The building was old and the elevator was from another era, but the location was bright, with a beautiful view of the city and the mountains. We often filmed the lights of Quebec City at night from our windows.

JM: And you shared those premises with other groups?

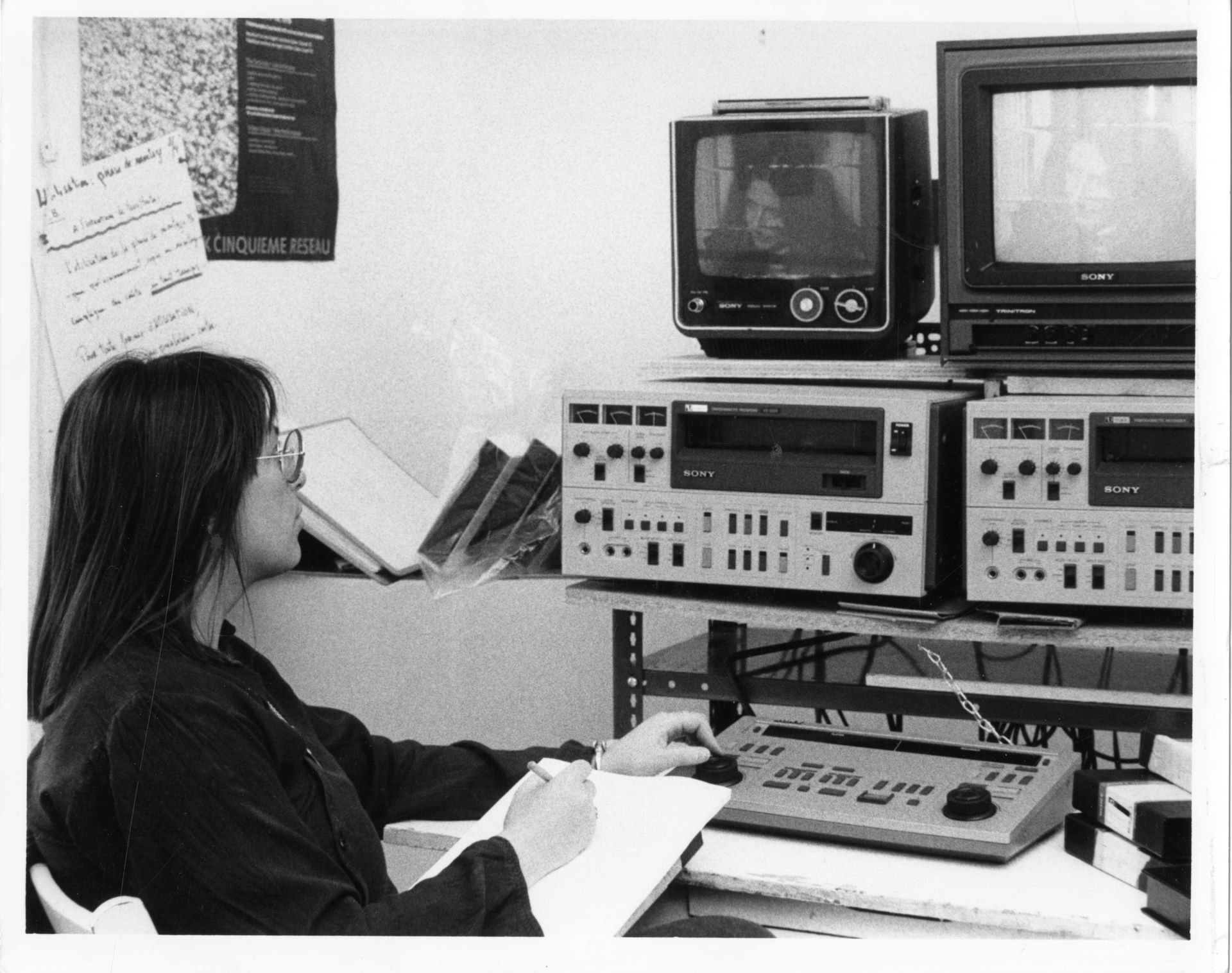

JF: It had formerly been private apartments. We had the equivalent of a two-bedroom apartment. The editing room and the technical equipment were in another apartment on the same floor. Other groups like Ciné-Vidéobec, Ciné-Vidéo du Faubourg, and Ressources Médias were in the other apartments. Together, we had the entire floor.

« C’est pas le pays des merveilles » (1981)

JM: In terms of production, you explored a variety of genres and styles. Which shoots stood out for you the most?

NG: For me, it was C’est pas le pays des merveilles. If I remember correctly, it was released in theatres in early March 1981, so it must have been shot in 1980.

JM: What was the production process like?

NG: It wasn’t an official Vidéo Femmes production, even though the whole team was involved in shooting it. Thanks to Fernand Dansereau, we shot it in 16mm. With Helen, we had the idea of writing about women’s mental health issues. Fernand Dansereau said to us, “I’ll produce it, but you’ll have to present the project to Télé-Québec and the SODEC to get funding.” Since Vidéo Femmes was an artists’ centre and not a registered production company, we couldn’t apply to the institutions.

Helen Doyle: Fernand was from the Quebec City area. He had worked at the NFB in Montréal as a producer and a director for a long time, but he wanted to come back to the Quebec City region and help filmmakers. He wanted to force Quebec’s institutions to provide funding to filmmakers in the different regions. His goal was to return to Quebec City and support regional productions through his production company, because everything always took place in Montréal. That’s how we ended up proposing our project on women’s mental health to Fernand. In fact, right around the same time, the Council on the Status of Women published a major study on mental illness, in particular depression in women.

NG: But we had to film it in 16mm, which was new for us. That’s why we brought Alain Dupras and Pierre Pelletier onto the team. They were friends of ours who worked as director of photography and camera assistant on 16mm shoots. And for the editing, we worked with José Heppell, who had an editing suite, because we weren’t used to working with the Steenbeck.

Fernand Dansereau célèbre la fin du tournage de C’est pas le pays des merveilles. Collection personnelle de Nicole Giguère.

JM: What was it like for you to work with a film medium while also going through all the steps from script to edit? What was that experience like for you?

NG: It was different in that we had a lot more writing to do! Up until then, our screenplays had been nowhere near 50 pages! We would just start with some research, or an idea, and develop it as we went along. But in this case, in order to present the project to those institutions, we needed a pretty well-developed screenplay. I remember that we did a lot of the writing at your house, Helen, when you lived on Sainte-Anne Street. There were a lot of fictional scenes and dreamlike sequences in that film, so to shoot it, we worked with several professional actors from Quebec.

HD: In keeping with Fernand’s commitment, we wanted to produce the film with a team from Quebec City or the surrounding area. But the film had to be developed in Montréal. So we would shoot it, and then the film would be sent to the labs in Montréal. We would then see the dailies three days later. It was a real challenge that made our producer a bit nervous.

NG: The reels of film were quite a bit more expensive than videocassettes, so we were quite limited during the shoot.

We weren’t used to that! Everything on the set was closely monitored by Fernand and his representative!

HD: What interested me personally was the formal aspect of it. There was the ongoing debate about female writing: Does feminist writing exist? There was that question. I think we contributed different methods and styles, compared to our colleagues, who were almost all men. Our script that combined fiction and documentary, and even dreamlike aspects, was one of the early experiments in mixing genres. Plus, we were telling the story of Alice in Wonderland in a way that was a bit crazy and out of step with what else existed at the time.

NG: It made the investors a bit nervous!

HD: Up until then, our business had always been among ourselves. But now, there were these institutions looking at our screenplay with some good-natured doubt. They would say things like, “Do you ladies realize this is the only film on mental health that will be made in the next five years?” That put some pressure on us. And they were nervous because we were from Quebec City and we had never worked with 16mm film.

JM: Did anyone put up any obstacles regarding the aesthetic aspects of the film?

HD: There were more questions than obstacles. We could feel that people were nervous. But Fernand wasn’t worried. He gave us a lot of encouragement! “Be bold, be bold, be bold!” The concerns really came from the institutions, not from Fernand.

NG: Regardless, we were able to do what we wanted. And to compose the music for the film, we brought in René Dupéré. I think it was the first time we had original music in one of our films.

HD: I think so.

NG: It was also the first time René had composed a film score. He later became famous as the composer for the Cirque du Soleil. By working with René, we got to know Sylvie Tremblay, whose singing career was just starting to take off. He was her accompanist. Sylvie wrote and sang the song “Folle, folle, folle.” That’s how our collaboration with her first began. After C’est pas le pays des merveilles, she was involved in several more of our productions.

René Dupéré, auteur-compositeur. Collection personnelle de Nicole Giguère.

Sylvie Tremblay: It was a very dynamic time in terms of artistic creation. [The people from] Vidéo Femmes and the Folles Alliées became friends of mine, and we even started a band called Pink Power! We collaborated for several years.

NG: For us, that collaboration was exceptional.

ST: They liked what I did, and so did I. There were some beautiful images. And it fit with my vision of music. I took on commissions, but how can I say it? With them, it was magical.

HD: What I remember most is that we were all getting used to working together. First of all, we were co-directors on a work of fiction, which also included interviews. So we had to work out how to allocate the roles. On each day of shooting, one of us was the director and the other was the assistant, and we alternated. We also had a script girl, Françoise Dugré. Basically, we were directing actors who were also just starting out, like us. So we were experiencing firsts at every turn. There was something very exciting about that. I’m not sure why, but we all trusted each other. In fact, that was the founding principle of Vidéo Femmes. “Okay, we have the opportunity to do this thing, let’s go, we’ll give it a try.”

JF: It’s also worth mentioning that your film, and others that followed, provided a number of Quebec City actors with their first professional filmmaking experiences. Rémy Girard, Yves Jacques, Léo Munger, Pierrette Robitaille, Marie-Ginette Guay, Marie Brassard, Marie Aubut, all of those people were involved in films by VF. Even Bob Walsh played a plumber who was a stalker!

JM: How was the film received? You mentioned that some of the producers were concerned about the blend of genres. How did the public react? Was the film widely shown?

HD: I think it went very well.

NG: Because it had been filmed on 16mm film, it could be shown in movie theatres, which wasn’t the case with video. As a result, the film was distributed in networks other than the usual Vidéo Femmes ones.

HD: And it was translated into English, which allowed us to show it at the Woman in Focus Festival in Vancouver, where it was very well received. We were also invited to the INPUT event in Ontario, in Niagara Falls. Even just recently, a women’s film distribution company in London contacted me to request the English version of the film. It’s wonderful to see that more than 40 years later, people are still interested in seeing the film. I think there were even different versions of it!

NG: Yes, there was a Japanese version, and a Spanish one, too.

LR: The Spanish version was shown at the film library in Bogotà, Colombia, in 1986, and at the Goethe Institute in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1988.

« Les mots / maux du silence » (1983)

JM: During that same period, some other experimental films were also made. Helen, can you tell us about Les Mots/Maux du silence?

HD: I had begun that film before Nicole and I got involved in C’est pas le pays des merveilles. When Hélène Bourgault and I showed the video Chaperons rouges, we began to hear a lot of personal stories. Women came to talk to us about what they had experienced after being raped. And the topics of psychiatry and madness often came up. Madness was always discussed in the broadest sense of the word.

I’d also done a lot of reading, so I included the words of women who had written about their own madness, like Marie Cardinal, for example. I had met Pol Pelletier, and I also heard from women who had truly experienced madness in all its forms, who had been hospitalized, who had received electroshock treatment. So I blended theatrical and literary words with real personal accounts and songs. It was a collage.

In Pol Pelletier’s account, she said, “When I start raving, it may seem incoherent to others, but there is a kind of coherence to it.” During the editing, I did a formal search for the language of “delirium,” but one that allowed for a certain understanding, and I assembled all sorts of disparate little pieces, like a quilt.

That’s when the Auto-Psy group, which was just being formed, approached Nicole and me. It was an advocacy group for psychiatric patients. They contacted us to request some guidance, so that they could produce their own films.

JF: Christine Gourgues, who was with Auto-Psy, made several. I did the editing for Ça a l’air de rien and Les gens qui doutent with her. Very good films. I also remember La Psychiatrie va mourir, and especially La matrice à l’asile, which was produced in 1982.

Nathalie Roy: We were very close to that group. I remember organizing several screening events with them. During those years, mental health was one of the main concerns of Vidéo Femmes.

HD: I was able to make Les Mots/Maux du silence because I had access to Auto-Psy’s equipment. That’s how I was compensated. So really, I made that film over five years, with different cameras, including some from Vidéo Femmes. I was immersed in fragility, and there was some madness even in terms of the equipment! In the end, the film was widely viewed, to my great surprise. I always considered the film to be important, but extremely fragile as well, precisely because of the different techniques involved, and the fact that it was made over five years, with about the same amount of money as for Chaperons rouges, i.e. around five thousand dollars. But I received more money after it won an award, so I was able to adapt it into English, and there was also a Japanese version, as was the case for Chaperons rouges and C’est pas le pays des merveilles. It began to be shown again, and each time, the money I received was invested into making new copies or new versions.

NR: We received a lot of screening requests for Les Mots/Maux du silence. It had been important to gather those personal accounts. There were also some performances, I think?

HD: Yes, lectures, performances, and theatre.

NR: It was a very personal project, but at the same time, it embraced all kinds of art forms related to madness. I think it may have won some festival awards, but my memory is hazy.

HD: Yes, it won some awards. The only questions I had touched on three subjects: women, madness and creation. I asked, “What is women’s madness? What is creative madness? What is women’s creation?” Those were the only questions I asked when I met with the people who were in the film. There was nothing else. No screenplay. There was Marie Cardinal, Marie Savard, my friend Aude who is now deceased, and two Swiss women who had been to Quebec many times, who had played Maude Santos, a French writer. It was a real patchwork. There were women who had agreed to tell their stories, and the creators also spoke about madness.

NR: We tackled such serious, personal subjects. But I felt that the way difficult subjects were dealt with, through acts of creation and with different points of view, was very much in keeping with Vidéo Femmes. Because women were the artists, and the film dealt with madness as it pertained to women. In my opinion, it was one of Vidéo Femmes’ most important films.

HD: There were some themes and sub-themes that were a bit taboo. For example, with Rachel, the topic of incest was touched upon, and with Hélène Grandbois, it was about a stifling bourgeois environment where girls were supposed to behave in accordance with certain stereotypes. There were some underlying elements of family violence in the women’s stories, and of hospital violence too.

JM: In terms of creation, was it your experience that in the context of madness, creation turned out to be a form of liberation?

HD: There was this idea of using creativity to escape psychiatry, but it was also a topic about which you had to ask yourself a lot of questions, particularly about the use of creative techniques that can be beneficial, but aren’t necessarily art. At the same time, for some people, outsider art is important art, so there was this whole debate about the power of art, and who gets to decide what is art and what isn’t. But for me, the most important thing was to give a voice to certain women about the way they experienced madness. Pol Pelletier, Marie Cardinal, and Marie Savard didn’t try to conceal anything. Although they didn’t talk about being committed, they still spoke of a form of madness, of losing control, and of pain so terrible that you don’t even know where you stand anymore.

LR: In the same vein, the announcement that Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” was coming to the Montréal Museum of Contemporary Art was a major event, and it quickly created a buzz in Quebec’s artistic and feminist circles. Another exhibit, “Art et Féminisme,” was created to be shown at the museum in 1982, alongside Judy Chicago’s piece. And the Cinéma Parallèle held a week-long feminist video event, where several works by Vidéo Femmes were shown. It was a success both in terms of attendance and of media coverage. That same year, Réseau Art-Femmes organized a series of women’s group exhibitions in Quebec City, Chicoutimi, Sherbrooke, and Montréal. Hélène and Françoise made a video during the event at the Musée du Québec, which was called Traces. I worked the camera for that project. It was a contemporary art event featuring works by women from different artistic disciplines. I remember that the artists took over the spaces in different ways, and we filmed them as they set up and installed their works. Some of the artists were well-known, others less so, but all were free to create their own artistic statements in the space. The works could involve performance, dance, theatre, visual arts . . .

JM: Was Traces in experimental form?

LR: Yes, it was an art video initiated by Hélène Roy and Françoise Dugré. We were exploring ways to present the multidisciplinary offerings of female artists. I remember a performance by the actress Lorraine Côté, who was accompanied by another actress, Lise Castonguay. They put on a theatrical performance in a space that was more suited to visual arts. There were also Lise Bégin, Aline Martineau, Louise Bilodeau, Valérie Letarte, and others that I’m forgetting! The blending of disciplines by female artists was relatively new. It had rarely been done. There was a real sense of solidarity. We were immersed in a process of artistic affirmation that the artists themselves were experiencing.

JM: It was a very exciting time, and you mentioned that a number of feminist works were created at the same time. It must have been quite extraordinary to be there at the time and to be part of those artistic events.

NR: Yes. And to have all those women expressing themselves in their own ways, right down to performance art, in a museum, which is normally a rather formal atmosphere, was very unusual.

« Tous les jours, tous les jours, tous les jours » (1982)

JM: Lise, it seems to me that you were behind the film project Tous les jours, tous les jours, tous les jours. You had just arrived at Vidéo Femmes. What were you doing before you joined the collective?

Lise Bonenfant: When I arrived in 1981, I had made a 16mm film called Clara, d’amour et de révolte at the small company I had founded. It had made the rounds of Quebec, and it had received standing ovations every time. That had really surprised me. And then disaster struck in my personal life. I lost a child. A little later, I called Hélène Roy. “Hélène, I think I need help. Do you think I could join Vidéo Femmes?” “I’ll talk to the others about it. We have a meeting this afternoon.” I remember I walked into Vidéo Femmes on October 7, 1981.

I had seen a call for tenders at Télé-Québec [then called Radio-Québec]. I wanted to get involved, since I’d just arrived—I don’t remember too much—I must have worked on it with Nicole. That whole period is a bit foggy for me. I was just trying to survive. We submitted the project Tous les jours, tous les jours, tous les jours, which dealt with the “ordinary” sexual harassment women experienced every day on the streets, at work, at the auto mechanic’s shop, everywhere. We won the tender. I think that’s when I became the producer, with that whole crew, and Johanne and Nicole, who made the film.

JF: Lise submitted our proposal in October or November, and I think we got the answer a week before Christmas. And we had to deliver it on March 1. It was a crazy deadline, really crazy. It was a hybrid production, meaning there were fictional, musical, and documentary segments. Jocelyne Corbeil had written the fiction parts. At that time, Nicole lived in a house in the country, on a rural road in Saint-Nicolas, and that’s where we got together. I think we worked on the screenplay on Christmas day. We chose actors from Quebec City. And Marie Aubut—who later became the singer Marie-Carmen—played the main character.

NG: Lucie Godbout also acted in another scene, because there were several fictional characters. So we got to know quite a few actors from Quebec City, who later moved to Montréal and became better known.

LG: I played a secretary who got her butt pinched by her boss. The project also brought together Vidéo Femmes and Les Folles Alliées; Jocelyne Corbeil and I were part of Les Folles Alliées. At the time, Les Folles Alliées performed theatre and songs, and we had created some humorous sketches for women’s events, such as March 8 and certain union events.

NG: Sylvie Tremblay sang several songs for that film.

ST: Yes, I sang, and I did the arrangements. The lyrics were written by Jocelyne, and I composed the music with Johanne Roy.

JM: How did you compose the music, Sylvie?

Lucie Godbout: Jocelyne wasn’t able to read or write music, but when she wrote the lyrics, she had a melody in her head that she would sing to someone who was able to transcribe it onto paper.

ST: Exactly. I remember working on the arrangements with Johanne, so that everything would sound good. I also composed some background music for the film, for the transitions.

JF: It was also the first production in which our names were listed in the movie credits. It didn’t just say “A Vidéo Femmes production.” Each of us had our own title and our own role. Lynda was the director of photography. Michèle Pérusse did all the interviews and a lot of the research for the documentary part.

NG: She also did the editing.

JF: Yes. Louise Giguère was the lighting assistant, and Lynda was on the camera. Françoise did the sound with Hélène Roy, and Nicole and I directed.

LR: For me, that production was pivotal. The entire Vidéo Femmes team was involved in the project, we were all familiar with the subject, it was an important one, and we knew that we would have a wider audience on TV. We also felt that the subject of sexual harassment would strike a chord with people.

JF: We shot a lot of it on location in Quebec City—the most humid city in the world in the winter—in the middle of January, all over the Latin Quarter. In every shot, you can see people’s breath as they exhaled.

JM: Is that the photo that was taken in the middle of winter? Do you remember?

NG: Yes! With the fur coats.

LG: It was -20° out, or -25°.

NG: We had to keep the batteries warm because the cameras kept conking out. We put them in our coats.

JF: That shoot was done very quickly and efficiently. We did the editing at Vidéo Femmes, and then we did the post-production at Radio-Québec in Montréal, because we had to deliver it on one-inch.

JM: I’d like to talk a bit more about the content of the film, the form, and the writing. What did you most want to put forth with that film? What were the most important style elements in Tous les jours, tous les jours, tous les jours?

LG: I think it was the hybrid aspect. It was both documentary and fiction, often in the same scene. I remember shooting in a restaurant, the Buffet de l’Antiquaire. I was on one floor, and another scene was being shot on the floor below. We went from a documentary to interviews in the same location. It was very fluid. I had never seen anything like it before.

NG: There was a lot of experimentation.

JF: There was also a desire to show a sampling of different backgrounds in the fictional sequences. So there was as much footage of the construction guys on the street as there was of a filmmaker approaching an actress in a bar, of a boss with his secretary, of a plumber in a house. The idea was to depict a variety of everyday situations in different environments.

LB: The distribution of Tous les jours, tous les jours, tous les jours was a big success. Radio-Québec was only required to give us one copy of the film, but I asked for several others, which I sent all over the place. Vidéo Femmes’ distribution network grew thanks to that movie. It was very well made. It was very touching. I think it contributed a lot to the expansion of Vidéo Femmes.

JF: The distribution network needed a lot of documentaries on specific subjects, and there were also a number of directors, Helen first among them, who were experimenting with dreamlike sequences and different forms. It was very important. We too were becoming more confident, and we didn’t want to become mere machines, churning out films on commission; we really didn’t want that. Sometimes you’d even hear, “I just want to make my own film. I don’t want to make a film for the network.” Some people wanted to get into more formal experimentation, in accordance with their interests.

NR: Video art was expanding, with possibilities that I saw very clearly later on at Le Vidéographe. Video made documentaries possible, but it also made experimental art possible.

JF: I also remember the first video art event organized by Andrée Duchaine, called Vidéo 84. It was a sampling of international videos, of art videos. Two of our productions were in it. There was Les tatouages de la mémoire, by Helen Doyle, and C’est une bonne journée, a short film I had made with Françoise Dugré.